If You Love a Game, Let it Go

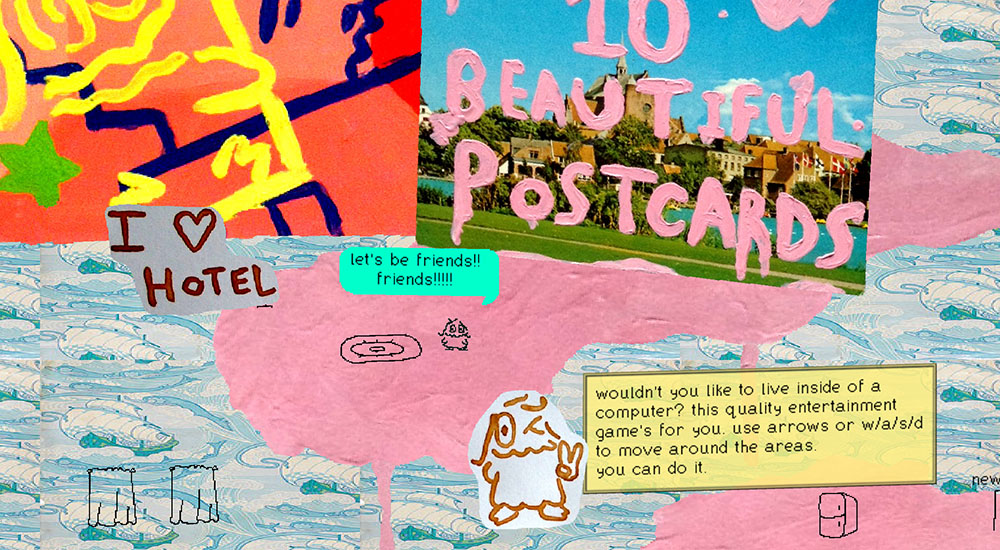

I really like the game 10 Beautiful Postcards. On paper, the premise is simple: wander through a veritable labyrinth of rooms and find all ten of the postcards.1

The game is full of surprising, funny, and joyful moments. It evokes a sense of wonder in me as few games do. But here’s the thing: I’ve never actually found all ten of the postcards. I think the most I’ve gotten is six.

Exhaustively searching this game, I think, would make it worse. It would turn what is a game of limitless possibility into a thing hung up on the wall, pinned like a butterfly. Stripped of its life as I rigorously catalogued every inch of it. Now, if I return, I know that this world may always have something more for me. Intermingled with the familiar and the novel is the space of the half-remembered. The latent great unknown that I explore with every visit through this game.

Games often enable this sort of completionism. They give you a map, or a checklist, or an achievement to guide you through dredging their deepest corners. Driven by giving you the maximum value, they bare their heart to you and dissect it.

Some games are meant to be visited, not catalogued. You don’t need to solve every side quest in A Short Hike. Bernband is at its best when you come across an abomination of a musical recital that you’ve never seen before. Yume Nikki is at its best when it promises secrets hidden away from you. Getting every shiny in Mini & Max would fall into the very mindset that it’s critiquing.

Some people think that seeing everything in a game is a way of showing your respect for a developer or a game, but it’s not. It’s exposing the artifice. It’s strip mining the mountain.

I don’t intend this to be a moral indictment of completionism. If 100% runs make you happy, have fun following that guide. But there’s another kind of respect: letting a place keep its secrets. The highest compliment you can pay to a magic trick isn’t to watch it from backstage; it’s to sit in the audience and allow yourself to be astonished.

In some ways, postcards are a great metaphor for this point. Postcards are souvenirs of where someone has been, yes, but they’re also invitations; “I wish you were here.” They hint at a world that you’ve got a single beautiful frame of, and outside of that frame there’s the museum you didn’t visit, the people you didn’t meet. In 10 Beautiful Postcards, some of those postcards remain hypothetical. They live in my imagination like negative space, and that space becomes part of the allure.

I think we underrate revisiting as a way of playing. We measure completion like we measure consumption: did I get my money’s worth? Did I extract maximum satisfaction from this product? What if, instead, we treated these games like visiting a national: you don’t hike each trail each time; you follow the twists and turns at your whim and turn back as you tire. Sometimes you go down the same path, but sometimes you take a turn that you haven’t seen before. The worth isn’t in the extraction, it’s in the experience.

I’m happy that I’ll never find all ten beautiful postcards, or, if I do, I’ll never know it. I like that they beckon me in from the outside, that the world remains larger than my understanding. The world of 10 Beautiful Postcards is limitless because I do not plumb its limits.

If you love a game, let it go. The best souvenir isn’t a filled-out checklist; it’s what brings you back.

-

Beautiful postcards, even. ↩︎